发布时间: Wed Nov 14 15:51:18 CST 2018 供稿人:许捷

本文原载于《商法》2018年10月|第9辑第9期,北京仲裁委员会授权转发。

北仲于2017年末受理了中国内地首例适用紧急仲裁员程序的仲裁案件(以下简称GKML 案)。该案申请人通过申请北仲紧急仲裁员颁布的临时措施,在香港顺利获得了香港高等法院原讼法庭的执行命令。经过仲裁庭高效的庭审组织和各方代理人高质量的法律服务,各方当事人以和解方式妥善解决了相关争议。随后,在GKML 案中担任紧急仲裁员的孙巍先生在其威科仲裁博客刊文介绍该案后,紧急仲裁员程序和临时措施的相关问题再次成为中国仲裁界热议的话题一。本文试从仲裁机构的视角为读者提供GKML 案不同的分析角度。

由于中国《仲裁法》和《民事诉讼法》没有规定仲裁庭享有作出临时措施的权力,且保全事项的决定权仍为法院专属,故国际仲裁案件中的当事人难以通过中国法的保全制度安排在跨境案件中获取保全利益。2015年4月1日版的北仲仲裁规则在其国际商事仲裁的特别规定一章中新增第62条临时措施以及第63条紧急仲裁员,不啻于一种大胆的创新,旨在满足前述实践中的跨境保全需求。

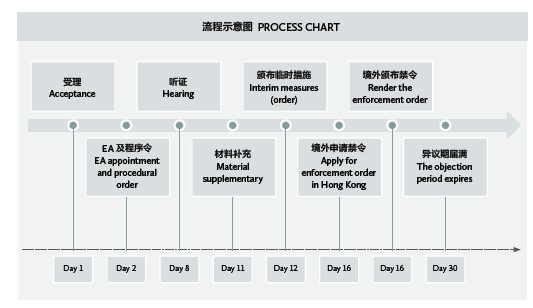

具体到GKML 案中,由于拟保全的财产权益在香港境内,且香港《仲裁条例》第22 b规定了“强制执行紧急仲裁员批给的紧急救助”一节,申请人在北仲立案的同时一并就申请启动了紧急仲裁员程序。该案具体流程详见本页下方示意图。

在该案中,紧急仲裁员程序的顺利启动以及紧急仲裁员专业的审理安排是高效推进紧急仲裁员程序的关键。孙巍先生在其文章中详尽地介绍了紧急仲裁员专业的审理安排,本文着重探讨的是如何顺利启动紧急仲裁员程序。

依据北仲规则紧急仲裁员程序的顺利启动取决于三个方面的因素:

(1)申请人及仲裁机构基于其自身实践积累对保全财产所在地法律环境的了解和判断;(2)仲裁机构是否有足够的信息和渠道能够及时完成送达程序,保障当事人陈述的权利;(3)仲裁机构是否能够在有限的时间内确定合适的紧急仲裁员人选,并协助其完成信息披露义务。

GKML 案中,首先,申请人在正式启动仲裁程序之前数日即与北仲立案部门取得联系,并沟通了启动紧急仲裁员程序的意愿。北仲则根据申请人主张的财产情况详细查询了数个法域关于紧急仲裁员程序的制度安排,以及相关法院诉讼保全措施/ 禁止令的具体衡量因素。在初步确定紧急仲裁员临时措施在相关法域具备执行可能,且申请人提交材料能够初步展示案情的情况下,后续紧急仲裁员程序的审理才具备高效推进的基础。需要澄清的是,在孙巍先生文章中提及做出临时措施的三个实体衡量因素——胜诉可能性、情况的紧迫性、临时措施的合理性及可执行性——并非仲裁机构在启动程序阶段考虑的事项,但仲裁机构围绕上述衡量因素促使当事人在一开始充分准备申请材料将极大地提升后续程序推进的效率。

其次,在该案正式立案前,北仲查询并获取了被申请人方主要负责人的电话及电子邮件联系方式,并在指定紧急仲裁员当日与被申请人取得有效联系。这让被申请人能够在短时间内了解紧急仲裁员程序的参与方式,建立了被申请人方对仲裁程序的初步信任,使其能够针对申请人的临时措施申请及时响应,提交相应的陈述意见。需要注意的是,北仲仲裁规则第63条第四款明确规定了“应保证当事人有合理陈述的机会”,但这不意味着紧急仲裁员必须等待双方陈述后才能作出临时措施。在一方明显拖延和懈怠的情况下,仲裁机构及紧急仲裁员仅需在相关程序安排上保证其具备陈述的机会。

最后,北仲在指定紧急仲裁员之前详细衡量了案件可能的实体争议类型,并与专精于此种实体争议类型的紧急仲裁员,即孙巍先生,充分沟通了后续程序的耗时和日程安排,协助其提前进行了利益冲突检索。这也是保证紧急仲裁员能够在仲裁规则规定的时间内及时处理相关事项的关键。

纵观GKML 案,作为中国内地首例适用紧急仲裁员程序做出临时措施的案件,其顺利推进不仅为中国内地的仲裁创新提供了实例支持,更体现了中国仲裁机构愈加成熟的国际化实践水平,北仲将继续根据国际仲裁的实践需求为当事人提供优质的仲裁服务。

作者:北仲品牌管理高级主管许捷。北仲仲裁秘书沈韵秋对本文亦有贡献

In late 2017, the Beijing Arbitration Commission/Beijing International Arbitration Centre (BAC/BIAC) accepted its first case applying the emergency arbitrator proceedings (EA proceedings)in Mainland China, known as the GKML case. In terms of the emergency arbitrator’s award rendered in arbitral proceedings administered by the BAC/BIAC, the applicant in the GKML case obtained an enforcement order rendered by the High Court of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Court of First instance.

With the arbitral tribunal’s efficient arrangement and attorneys’ professional contribution, the GKML case was finally settled amicably. The emergency arbitrator in the GKML case, Sun Wei, posted an article recently in his Kluwer Arbitration Blog to introduce this case. It has attracted a lot of attention and generated subsequent discussions among the Chinese arbitration community on the EA proceedings and interim measures.

This article offers a different perspective to that of the arbitral institution on the EA proceeding and interim measures of the GKML case.

Since the arbitral tribunal is not authorized to order an interim measure under the Arbitration Law and the Civil Procedure Law, and preservation has exclusively remained at the court’s discretion, the parties in international arbitration cases have difficulty realizing their preservation interests under this legal framework. The Beijing Arbitration Commission Arbitration Rules, effective from 1 April 2015,added and revised the interim measures(article 62) and the emergency arbitrator (article 63). The revision is deemed as a progressive innovation and is designed to satisfy the need in international practice.

In the GKML case, since the property was to be preserved in Hong Kong, and the Arbitration Ordinance in Hong Kong has the provision of Enforcement of Emergency Relief Granted by Emergency Arbitration (section 22B), the applicants registered the case at the BAC/BIAC and initiated the EA proceeding at the same time. The detailed process in the GKML case is illustrated in the process chart below.

In the GKML case, the smooth commencement of the EA proceedings and the professional arrangement of the emergency arbitrator are two keys to the effective progressing of the EA proceedings. Sun Wei gave a detailed introduction of the arrangement from the EA perspective, while this article concentrates on how to smoothly initiate an EA proceeding.

According to the BAC rules, the successful commencement of the EA proceedings depends on the following three factors:

• Whether the claimant and the arbitration institution, based on their own practical experience, comprehend the legal environment of the place where the attachment property is located.

• Whether enough information and approaches are available for the arbitration institution to conduct effective and efficient service, thus ensuring that the parties are able to present the case.

• Whether the arbitration institution is able to make a fit appointment of the emergency arbitrator within a certain period of time and guide the disclosure proceedings.

In the GKML case, at first, the claimant communicated its willingness of using the EA proceedings with the BAC/BIAC’s case acceptance division, a few days in advance of the formal commencement of the arbitration procedure. After this, the BAC/ BIAC reached out in different jurisdictions and got positive affirmation of the recognition of EA proceedings in target jurisdictions, along with normal factors that local courts in target jurisdictions will inspect in deciding similar measures of preserving properties or injunctions.

Having done this, the BAC/BIAC allowed the claimant’s application of EA proceedings, while the case filing material was enough to present the case on prima facia bases. Sun Wei’s article listed three substantive factors that affect his discretion – the likelihood of success, urgency of the case, and reasonableness of interim measures. It should be clarified that these three factors are not necessarily taken into consideration when the arbitration institution decides whether to allow the application of EA proceedings.But taking them into consideration is likely to help the parties better prepare for a more effective and efficient EA proceedings.

In the communication mentioned above, the BAC/BIAC acquired the main contacts of the respondents, including cellphones and email addresses, allowing the BAC/BIAC to effectively communicate with the respondents and educate them on the EA proceedings from the first day. Such communication also helped build trust between the respondents and the arbitration institution, which encouraged the respondents to produce documents in time, and to better present their cases.

It should be noted that, in accordance with article 63(4), that “the rights to state shall be ensured” does not necessarily mean the emergency arbitrator cannot decide the interim measures by ex parte presentation. When deliberate delay exists, the test will be whether the arbitration institution or the emergency arbitrator has arranged the opportunity for presenting the case.

Finally, before making the appointment of the emergency arbitrator, the BAC/BIAC measured the possible substantive issues of the case, and then made contact with Sun Wei, an expert in the sector, in order to co-ordinate with his schedule and avoid potential conflict of interest. This is how we made sure the emergency arbitrators were able to deal with issues within the prescribed time, according to the BAC rules.

Since the GKML case was the first one that made the interim measures in the EA proceedings among cases in Mainland China, its success not only sets a precedent for Chinese arbitration institutions’ innovative practice, but also demonstrates the internationalization of Chinese arbitration institutions.

Terence Xu is a senior manager at the BAC/BIAC. BAC/BIAC’s case manager, Shen Yunqiu, also contributed to the article